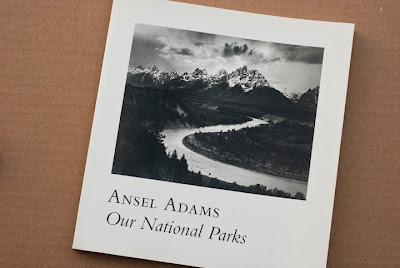

Ansel Adams: Our National Parks

Edited by Andrea G. Stillman and William A. Turnage

Little, Brown and Company

1992

Ansel Adams was never one of my favorite photographers. It felt as if I was expected to like him since he was the most famous photographer in the landscape genre when in fact the pictures he made were rarely personable enough for the average viewer to relate to meaningfully. At the time pictures of nature often felt too far removed from my suburban life for me to easily access them. Adams' images served as a referent to a natural world in which I had no interest in recreating, nor in emulating photographically. Perhaps even while disliking the work, I still respected it as my father respected Adams for the luscious, technical perfection he brought to his representations of the apparently untouched American West.

Looking at this book after not considering it in a long while reminds me that I have owned it twice. Once as a teenager I purchased it to give to my father as a birthday or Christmas present. Later I purchased it on my own as part of a clearance, closing-sale of a small bookseller in the Kansas City area. At the time it was the beginning of the end for independent bookstores. Even prior to the ubiquity of Borders and Barnes and Noble, stores like B. Dalton and Waldenbooks had come to define what local bookstores were in the Kansas City area. Our National Parks was probably an odd splurge for a teen boy who was more interested in buying science fiction by Piers Anthony , CDs of British rock, or in having a few extra quarters to play Street Fighter II.

The book is a slender, modest paperback collecting highlights of Adams' imagery of our National Parks. The reproductions are good, not great, but certainly fine enough to admire Adams' prowess with the medium. The range of tones from deep black to detailed highlight are almost disheartening, as if teasing young photographers to wonder, "How could I ever produce something so beautiful?" Disregarding all subject matter, historical significance of the parks, or the current ghetto that is fine art landscape photography, Adams' mastery of the medium is rarely equaled and potentially unsurpassed in influencing those of us who pick up cameras to create something of beauty. It seems doubtful that Adams' work would be considered in a BFA context these days beyond an art historical reference, but his vision of pristine wilderness mediated through the view camera still holds sway in the work of photo-hobbyists and in publications such as View Camera, LensWork, and Camera Techniques.

During high school I perused the books from Adams' still-excellent technical series: The Camera, The Negative, and The Print (later Polaroid as well). The zone system seemed far beyond my skill set and to this day I have never properly made an exceptional black and white negative and print to my liking. Still it was through Adams' instruction that I was able to gain a significantly better understanding of basic shutter/aperture controls to view camera movements. While not a devotee of photography as pre-visualization of the natural world, he did contribute to my learning that picture could be a new thing, far from a literal transcription of a scene. It was never National Geographic or Sierra Club imagery that Adams made, even despite his association with the latter. In Adams' pictures the skies had an undeniable presence that was god-like, the leaves described unknown textures, and the light that fell upon the Grand Canyon seemed like an index of the hand of God.

Adams was the artist who took the idea of Straight Photography to the landscape and came back with something completely new. It wasn't a mountain, a stand of aspen, or the moon over Hernandez, NM that Adams' pictures revealed, but the idea of what nature and a photograph could be if you applied enough imagination to them. Even better, Adams seemed to have viewed all of photography and nature holistically, educating about photography even as he campaigned for the preservation of our natural world. That we could still read any of his technical series and essentially know everything necessary for darkroom-photography is much to his credit as a legacy of significant imagery in publication and museum collections.

The book contains a selection of Adams' National Parks related writings as well as a picture of him with Gerald Ford in the Oval Office. Such was the power of Adams' pictures that he became the aging statesman of photography and great advocate for the perpetuity of our natural spaces through conservation.

At a large family gathering for Christmas several years after purchasing this book, my cousin gave several members of my family framed Adams' images of about 16x20 inches. It felt quite generous at the time to give us such large, difficult-to-transport presents. Little did I realize until several years later that the gifts were acquired from the then-bourgeoning scene of Los Angeles parking lot art sales where "framed art" could be purchased for around $5.99. It is in the omnipresence of Adams in poster sales that his pictures have been immortalized as beautiful decoration, much like Van Gogh, Monet to the likes of Nagel or Peter Max. Needless to say such sales didn't exist in the Kansas City area and "Moonrise Over Hernandez" did festoon the space above my bunk-bed for years to come.

Most of our tastes change in time and much as we might be embarrassed for what we once loved, there is also a certain discovery to be had for coming back to the child we were in seeing something for the first time. Ansel Adams made stunning pictures that few have equaled, even if landscape photographers continue to unnecessarily ape him year after year. If you dislike Adams' bombastic view of nature, those who now tread similar territory largely come across as copycats. As first, and best, to approach the American West as an artist unaligned with geographical surveys, Adams will always hold high esteem for me in showing pictures as worlds all their own, attached to nature and yet still about photography's inherent potential for transformation. Each picture shows a mastery of camera, negative, and print that would humble any picture-maker taking up a camera for the first time.

Comments